Case study 3: Marching and demonstration policies

“Scotland Against Mosques” (SAM) has applied for permission from the council to stage a demonstration in a major city centre square this coming Saturday to protest against the “Islamification of Scotland”. They propose to march through the city centre before holding a rally in the square.

SAM’s mission statement is to ensure that no further mosques are built in Scotland, as they believe Islam is “un Scottish,” through all peaceful and legal means.

The proposed route of the march passes the central mosque.

The last time that an anti-Islamic lobby group staged a demonstration to protest in the city centre they attracted support from other far right groups and a counter demonstration by left wing groups. This resulted in some violent clashes and three arrests.

The council’s policy in relation to applications to stage demonstrations is that permission will be refused if there is any possibility of violence. In considering whether or not to grant the application, the council takes account of concerns which are expressed by local shopkeepers, community leaders, and religious groups about a re-occurrence of violence.

The council is concerned that a decision against SAM might interfere with their right to freedom of assembly and their freedom of expression. However, they are also concerned that a decision to allow SAM to march will raise tensions within the Muslim and other communities and might mean that the council will not meet their requirement under the Equality Act to foster good relations.

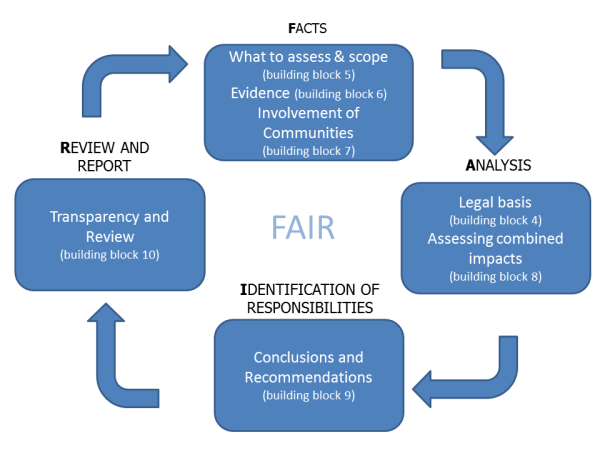

They decide that they should carry out and equality and human rights impact assessment to guide their decision.

Task

How should council proceed? Using the questions below, follow the FAIR model to develop the response:

Facts: What are the important facts?

Are there specific, potentially disproportionate, negative impacts on particular groups including those with protected characteristics?

Which individuals and groups need to be heard?

What sources of evidence (qualitative and quantitative) could be used to assess the current and future impacts of the policy options?

When gathering the facts:

-

What methods would you use to ensure that those affected by the policy are consulted and involved in decisions that affect them, in an active and meaningful way?

-

Can you identify any of the individuals or groups who are likely to need support to engage with you, and if so, who will provide that support?

-

What information will those affected by the policy need in order to be able contribute effectively to the consultation process?

Analysis: what are the human rights at stake and what are the implications of the policy for compliance with the Equality Act?

-

What are the human rights issues at stake?

-

Are the rights absolute?

-

Can the right be restricted and if so, what is the reason for the restriction in this case.

-

If the right is being restricted, is the response proportionate? (i.e. is it the minimum restriction necessary to achieve your objective – or is it a “sledgehammer to crack a nut”?)

-

From the evidence gathered are the protected groups likely to be treated less favourably than others by the policy?

-

If the policy applies to everyone, are the protected groups likely to suffer a particular disadvantage compared with other groups?

-

Is the policy designed to achieve positive benefits for protected groups? For example, will the policy remove or minimise disadvantage, meet particular needs or encourage participation?

-

What is the potential impact on “good relations “ – that is the “promotion of understanding and the reduction of prejudice.”

Identification of shared responsibilities

-

What changes if any, are necessary to the policy that would mitigate any negative impact of the policy?

-

Who has responsibilities for helping with any necessary changes?

Review actions and policy

-

Have the actions taken been recorded?

-

How often, and in what circumstances, will the policy be reviewed and by whom?

FEEDBACK FOR CASE STUDY 3: MARCHING AND DEMONSTRATION POLICIES

The important facts in this case are that the rights of different groups are in tension. SAM wants to raise awareness about their opposition to the “Islamification of Scotland” but their purpose is both disputed and opposed by large sections of the community, both Muslim and non Muslim.

The key human right at stake here for SAM, and any potential counter demonstrators, is freedom of assembly (Article 11) and the right to freedom of expression (Article 10).

These are both qualified rights and therefore the focus should be on the proportionality question: in what circumstances might it be permissible to refuse SAM the right to protest and would a refusal be appropriate in this case?

The right to freedom of assembly can be restricted where the council have a good reason such as national security, public safety, preventing crime, protecting heath or protecting others rights.

So when considering what decision to make, the council will take into account the fact that it is anxious to avoid a repeat of the violence last time an anti-Muslim group marched in the city. However, in order to ensure a proportionate response, the council has to decide which course of action will cause the least interference to the rights of SAM.

The options open to them are:

-

To allow the march and demonstration to go ahead as planned and to make sure that it is adequately policed and stewarded.

-

To require SAM to use a different route so as not to provoke counter demonstrators.

-

To refuse permission for the march and /or the demonstration.

In reaching their decision they need to take into account the views of SAM, as well as members of the public affected by the route, opponents of the group and also shoppers and shopkeepers trading in the area who might be disrupted. The council would also need to liaise with police about their decision.

The council also has an obligation under the Equality Act to pay due regard to the need to “foster good relations”. This is a positive duty, not a reactive one. What constitutes “good relations” has not been tested in law. However it is clear that a demonstration which has the potential to incite religious hatred is not compatible with a general requirement for the council (and police) to “reduce prejudice”.

Their final decision should be the one that, in their judgment, interferes the least with SAM’s rights to march and demonstrate, but also allows for the legitimate expression of protest against SAM’s views. They might decide to allow the march on the condition that it is re-routed, that specific conditions are placed on the organisers to undertake not to display or utter offensive symbols or words or to undertake a course of action which would be likely to incite religious or racial hatred. Alternatively, the council may decide that the presence of the marchers would inevitably lead to illegal acts taking place (inciting religious hatred) and decide that this requires a restriction on the right to march or assemble at all.

This situation may result in a decision to review the policy. It will therefore have to be viewed through the human rights and equalities lens and using the balancing act of proportionality for every individual request as the circumstances will always be different. However, the council’s policy currently allows restriction whenever there is any possibility of violence. That is likely to be viewed as too restrictive as the council should weigh up in the individual case the likelihood of violence. A policy which allows for a blanket ban on a particular group marching because of violence in the past will almost certainly breach the right to freedom of assembly.

This case is based on the types of decisions which councils require to make in relation to rallies, demonstrations and marches, such as the Orange Walk. A case along similar lines was considered recently by Aberdeen City council, which published a note of the outcome on the internet, see here.